The Whistler Lakes Conservation Foundation advocates for Whistler lakes and watersheds to ensure their long-term health and sustainability. We acknowledge that in Whistler we live, work and play on the shared unceded ancestral lands of the Sk̲wx̲wú7mesh Úxumixw, people of the Squamish Nation and the L̓il̓wat7úl, the people of the Lil’wat Nation. Under their stewardship, the land and lakes have flourished. We are fortunate to learn from their shared cultures and will carry on with the same respect and stewardship of Whistlers lakes.

The ancestors of these two strong Nations have lived, hunted and traded on this land from time immemorial. They shared the responsibility of the land, lakes and waterways and cultivated and cared for the ecosystems across their territory. Indigenous peoples were the original creators of the concept of “leave no trace”. The Squamish Nation and the Lil’wat Nation were stewards of the Whistler area, treating it as a “living land” and a precious resource.

Left: Harriet Harry (Tsawaysia) barbecuing salmon ‘Squamish Nation Style’ at the Sta-a-mus Reserve. Right: Moses Billy (Siyamshun), of Squamish Nation, working on a dugout river canoe at Sta-a-mus Reserve. He lived in Sta-a-mis in the early 1900’s. Source: Squamish History Archives

For both the Squamish and Lil’wat Nations, geography is at the heart of everything. We are not exaggerating when we say that the mountains, rivers, lakes and ocean have shaped our histories, customs, arts and artisanship. Indeed, the landscape of southwest British Columbia has shaped who we are and the way we live. (18)

Practically everywhere you look in the traditional territory of the Squamish people, there is water: a river, creek, lake or the ocean. And the word “Lil’wat” means “where the rivers meet,” referring to the three major rivers of the traditional Lil’wat territory watershed: Tśtátśquwem (Green River), Líl̓watatkwa (Lillooet River) and Qwal̓ímak (Birkenhead River). Historically, the rivers, lakes and oceans of our territories teemed with salmon, herring and trout, all valuable food sources. These waterways were also the roads and highways of our Ancestors, an efficient way of getting from one Nation to another for trade and social gatherings…moreover, water features large in our oral histories, reflecting the fact that water was and in many ways, still is, the lifeblood of both the Squamish and Lil’wat Nations. (34)

– Where Rivers, Mountains and People Meet by The Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre

Chief Jimmy, unknown child, August Jack, of the Squamish First Nation.

Source: Squamish History Archives

There are rich stories of seasonal pit houses and camps on Green Lake for gathering resources and of a Wolf Clan village located at the base of Tsiqten (Fitzsimons Creek) where fishing would occur. Bog cranberry, wapato (wild potato), skunk cabbage, cattails, small-flowered bulrush, rough horsetail, rocky mountain pond lily and ducks are just some of the plants and animals that have been collected as important food or medicines. At the River of Golden Dreams (South end of Green Lake) the Sun Hkaz – Lil’wat (double-headed serpent), flowed between Alta Lake and Green Lake.

Wayside Park in July 1979. The park was the only public access to Alta Lake at the time. Source: Whistler Museum

Gold miners, loggers, fishermen and settlers of various other occupations came to know these lands and the mountain originally known as Cwítima/ Kacwítima (by the Lil’wat Nation), and Sk̲wik̲w (by the Squamish Nation). The first European name for the mountain was London Mountain, named after a mining claim in the area. Settlers built homes, lodges and lumber companies around the Whistler lakes, giving them European names: Alpha, Nita, Alta, Lost and Green Lakes.

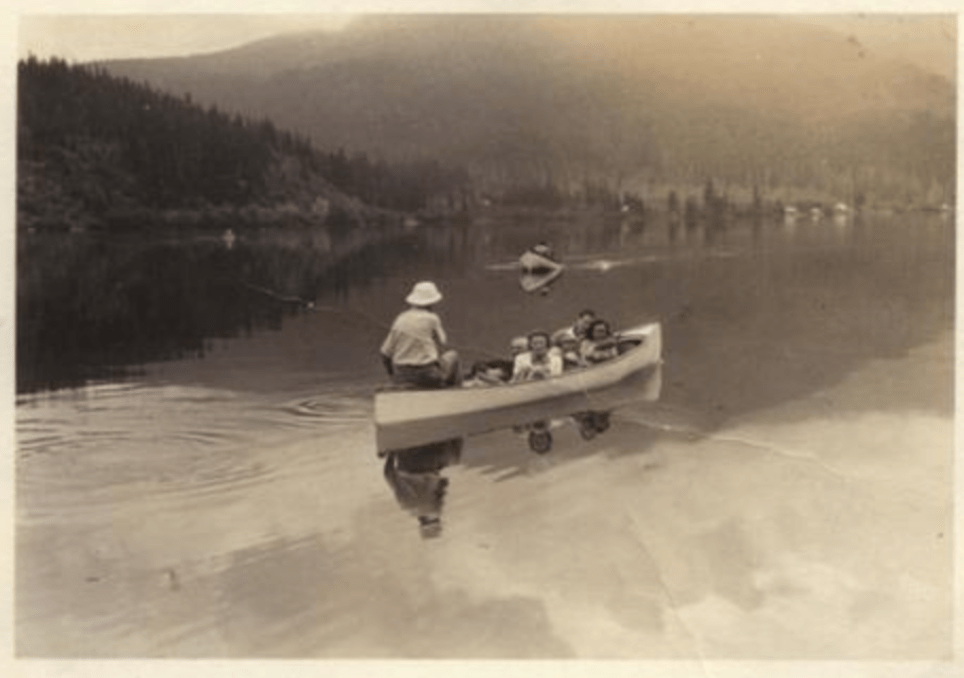

Left: Myrtle and Alex Philip (rt) with a Rainbow Lodge guest and a line of fish caught in Alta Lake. Right: Settlers canoeing, location unknown. Source: Whistler Museum.

The completion of the Pacific Great Eastern railway in 1914 attracted more settlers and tourists to the area. With the development of the ski resort in the 1960s, the name London Mountain was changed to “Whistler,” representing the whistling calls of the marmots, also known as “whistlers”, that lived in the mountain alpine areas. Recreational development since the 1980s has increased public access to the lakes, rivers and creeks via trail systems and parks.

Green Lake Rock Painting by Lil’wat Nation artist Johny Jones in July, 2009. It tells stories around the Whistler area. Source: RMOW “Trails Through Time” Interpretive Panel

To date, the original Indigenous names for Whistler’s lakes have not been found but with personal communications with Heather Paul and Alison Pascal of the SLCC and The Lil’wat World of Charlie Mack the following place names describe certain areas:

Kítsectsecten – The northern end of Green Lake, means “deer’s rest down area”.

Etsáltsem –An area near Green Lake, “Painted Rock”.

S7úm’ik – By the site of the Rainbow Lodge/Alta Lake Station, means “where trout spawn in creek”.

Xwel’píl’cten – A small hill between Alta Lake and Nita Lake. Comes from the word xwelp’ílc – to go over something, place, or object.

Nqwím’tsten – Rainbow Lake.

Ú7mik – “meaning ‘upstream’ is applied to the creek flowing out of the South end of Alta Lake, also called “Scotia Creek”.

Resources

- Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre (SLCC)

- Whistler Museum

- Maxine Bruce Ted Talk: “How Being One with the Land can Bring us Together”

- Whistler 101: Biodiversity

- Whistler Museum: Creating Whistler’s Parks

- Cheximiya Allison Burns Joseph Interviews, March 2022 (manager of the Indigenous Youth Ambassador Program) and May 2022

- Tanina Williams (Lil’wat Knowledge Keeper, founder of amawílc) interview, August, 2022

- First Tracks: Whistler’s Early History

- Where Rivers, Mountains and People Meet by The Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre

- Gifts of the Land: Líl̓wat Nation Botanical Resources by The Lil’wat Nation

- Q’ELQÁMTENSA TI SKENKNÁPA – BLACK TUSK AREA by Johnny Jones, Vol. 43 No. 1 (2011) – The Midden

- SLCC Podcast Series